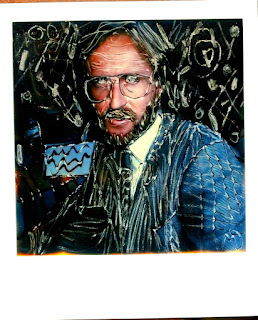

(originally published in Movieline Magazine)

- James Cameron

looks much too relaxed for a man who has just made what may be the most

expensive motion picture ever made. The fate of an entire major studio

may rest on his shoulders, but he seems to shrug it off. Maybe he's just

relieved the whole mammoth production ordeal is over. Maybe he's giddy

over getting married next week to fellow director Katherine Bigelow. But

he's probably in such a good mood because in two more years he gets to

go to his twenty year high school reunion and casually mention that he

turned a short story he wrote as a student into a $50 million sci-fi

extravaganza. (And what have you done with your high school papers?)

The Abyss, which Cameron wrote and

directed, was a massive undertaking. It's certainly the most complex

underwater extravaganza ever filmed, and 20th Century Fox could have

sunk a real oil rig for the same cost as making it. But Cameron seems to

be a safer bet than oil. When he cranks up the cinematic pressure,

everybody in the theater stops nibbling popcorn and starts on their

fingernails. His chase sequences contain so much urgency that it's

surprising more people haven't had heart attacks while watching them. He

puts you in situations you really wouldn't want to be in, and he never

goes for the easy out. We go to his movies to face some deep primal fear

we didn't know we had; there are no cheap shocks in a Cameron film,

just a neverending onslaught of supreme danger.

The Abyss, which Cameron wrote and

directed, was a massive undertaking. It's certainly the most complex

underwater extravaganza ever filmed, and 20th Century Fox could have

sunk a real oil rig for the same cost as making it. But Cameron seems to

be a safer bet than oil. When he cranks up the cinematic pressure,

everybody in the theater stops nibbling popcorn and starts on their

fingernails. His chase sequences contain so much urgency that it's

surprising more people haven't had heart attacks while watching them. He

puts you in situations you really wouldn't want to be in, and he never

goes for the easy out. We go to his movies to face some deep primal fear

we didn't know we had; there are no cheap shocks in a Cameron film,

just a neverending onslaught of supreme danger.Cameron is a Corman alumnus who starting out as art director and production designer for dozens of cheapo shlockos. He made his directorial debut with another undersea adventure, Piranha II - The Spawning, about which the less said the better. It doesn't even appear on his resume, and who can blame him when his second film was such a monster.

The Terminator was a barrage of science fiction mayhem directed with non-stop momentum, presenting a relentlessly bleak but visually fascinating vision of tomorrow. Up until that time, it had been considered a drawback that Arnold Schwarzenegger's performances were robotic. But Cameron cast him impeccably as a killer cyborg from the future, and the film was an enormous hit, giving both their careers a boost.

After writing the screenplay for Rambo: First Blood II, he then wrote and directed Aliens. It was an even bigger hit than its predecessor, earning seven academy award nominations and more than $180 million.

All this paved the way towards The Abyss, a technological marvel full of brilliant set pieces. The world is still dangerous, things can still go wrong in the most unlikely ways, but Cameron's focus is more on character than it's ever been. It's the couple that counts, not the mysterious inexplicable force surrounding them.

The idea for the film came from a science experiment that Cameron saw performed in high school, which he eventually turned into a short story. "There was a guy named Frank Felacek, a human guinea pig who actually breathed a liquid in both lungs," Cameron explained from his posh hotel suite in Beverly Hills. "They started with one lung and then the other. He thought he was going to die, and everyone got real nervous, so they pumped the stuff out of his lungs. It didn't work very well because a saline solution couldn't hold enough oxygen. But later they started experimenting with flourocarbon, and they've done it very successfully with dogs and monkeys. The FDA won't let them use it in human experimentation, so the research has sort of hit a wall, but the proposition is that if there was ever a strong enough military application for it, it would proceed again. In the film, when the rat breathes it, it's the real stuff, it's really happening, the rat is breathing flourocarbons."

- It's one of most

disconcerting visuals in the film, when Ed Harris seems to be breathing

liquid rather than air in a diving outfit that's full of water. It

looks like a truly death defying act, and you might assume that there

was hidden breathing apparatus somewhere in the suit. Wrong. "He just

had to hold his breath for a long time," said Cameron. "Any hidden

breathing apparatus would have leaked, so there would have been bubbles

coming up all the time. Ed didn't like it. It was very uncomfortable,

but I don't think it was ever really dangerous.

"In the film, you see the helmet seal down into a neck ring that looks like one integral unit. In actuality, the whole faceplate popped open on a hinge and he would just breath through a standard regulator. When we were ready for the take, the regulator would be removed, the bubbles would be cleared away, and the faceplate would be closed. It had a very delicate latch that could be easily over-ridden if necessary. It took a lot of nerve, but Ed did almost all his own stunts. The wider shots where he's tumbling down the wall are the only places where we doubled him."

I accused Cameron of being a victim of techno-lust and he laughed it off. "In Good Morning, Vietnam, a guy says 'In my heart, I know I'm funny.' Well in my heart, I know I don't have to do science fiction. I think it's all these residual images from my childhood, when I read science fiction voraciously, like Bradbury, Clark, and Heinlein. It's such a visual form. I was always interested in the fantastic, like the Sinbad films, anything with spectacular mythological energy. I tend to be less interested in pure fantasy. I like to be grounded in a sense of the possible, or at least creating an illusion of the possible for the audience. In science fiction, there's always the greater possibility to take people someplace they've never been and showing them something they've never seen, more than there is in a contemporary story set in Manhattan."

Will he ever make a non-science fiction film? "I'm now being forced to realize that that's a challenge I have to set for myself. I have to take people someplace new, given relatively mundane props and visual set pieces. I have to do it through psychology, through performance. I think I'm over that threshold now. The scenes that people respond to the most are not the techno-lust scenes. The two scenes right at the heart of the picture which are the most emotionally intense, involve absolutely no support from any mechanisms like special effects or production design. It's two people talking in a four foot diameter tin can."

He's got that one right. In The Shining, Stanley Kubrick was the first to postulate that absolutely nothing is more frightening than a husband and wife trapped together. Cameron takes this concept one step further in The Abyss, giving us one of the most harrowing life-or-death scenes of all time.

He takes an estranged husband and wife who secretly love each other but whose passion can only reveal itself through sarcasm - and puts them under pressure. A lot of pressure - like at the bottom of the ocean in a leaky two man submarine with only one set of diving gear. The leak can't be fixed, and they've only got a few minutes till the whole sub is full of water. One of them has got to die. They've probably both secretly wished for the other's demise, but not like this. The one who lives will have to watch the other drown. Close up.

Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio are so good in this scene, their fear and devotion so raw and vital, that I can't think of any episode in any other picture that rivals it in emotional intensity. It's so ferociously performed that it overshadows the big special-effects finale. The alien force becomes just a sub-plot. (Come to think of it, the whole film is a sub plot)

I casually mentioned something concerning the aliens, but Cameron is reluctant to talk about the specifics of the ending. He doesn't want it given away, and he wants the audience to figure it out for themselves. He also dismisses any charges that the film is too derivative. "Most people think if you're doing a story about human contact with a bad monster, it's going to be Alien, and if you're doing a story about human contact with an intelligent species from another place that's mysterious and strange, it's going to be Close Encounters. I refuse to accept the idea that there are only two choices left and nobody else can make a film on any subject even remotely similar. E.T. and Close Encounters are amazing and beautiful films. This film uses the concept in a different way."

"I think this is a less cynical picture than my others. I've always been very positive about people and negative about trends. This film has the same kind of balance between positiveness and paranoia. There's still the paranoia of nuclear weapons, the potential for war, even though we're in a 'glasnost' period. As long as the president of the United States is the ex-head of the CIA, and the premiere of Russia is the ex-head of the KGB, there's a limit to how much you can really relax. Ultimately, it's a more optimistic picture because it deals with people I see as positive role models."

In an attempt to play devil's advocate, I told Cameron one of the arguments against the film. The Abyss is essentially about a relationship between husband and wife. People who are into relationship films don't necessarily go see big science fiction films, and techno-nerds who go see big science fiction films don't necessarily care about relationships.

His reply was fast. "The counter argument to that would be that techno-nerds need love too, and relationship people also live in a technical world. I don't think there's a hard distinction between those two groups. There's a big intersecting set of people in the middle who both acknowledge that we live in a technological world and feel all those normal human emotions that everybody feels. They have to address that in their lives as well. I see it as a film for anybody living in the latter half of the twentieth century who happens to be human, male or female. I hope that's not too narrow a band."

I wanted to ask him why the crew referred to the film as The Abuse. I wanted to ask him why the alien neon hairdrier saved some people but not others. I wanted to ask him about the water tentacles and what the film was really about, but our time was up much too quickly.

He was dragged to the door by a publicist, but before he left, I asked him one more question. "If there's a water that men can breath, then why isn't there an air that fish can breath?"

"I don't know," he replied. "I guess fish aren't doing enough research in that area."